December 30, 2011

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author and/or guest contributors and do not necessarily state or reflect those of

The Perfume Magazine LLC, Raphaella Brescia Barkley or Mark David Boberick.

All content included on this site, such as text, graphics, logos, icons, videos and images is the property of The Perfume Magazine, LLC. or its content suppliers and protected by United States and international copyright laws. The compilation of all content on this site is the exclusive property of The Perfume Magazine, LLC. and protected by U.S. and international copyright laws.

The Perfume Magazine Banner was designed exclusively by GIRVIN and is the property of The Perfume Magazine, LLC. and are protected by U.S.and international copyright laws. Additional Banner information can be found on our ABOUT page.

All images appearing in the banner are registered trademarks of their respected company and are used with permission.

© Copyright. 2011. All Rights Reserved. The Perfume Magazine LLC

Co-Founder, creator and artist of A Dozen Roses, Sandy Cataldo, signing bottles

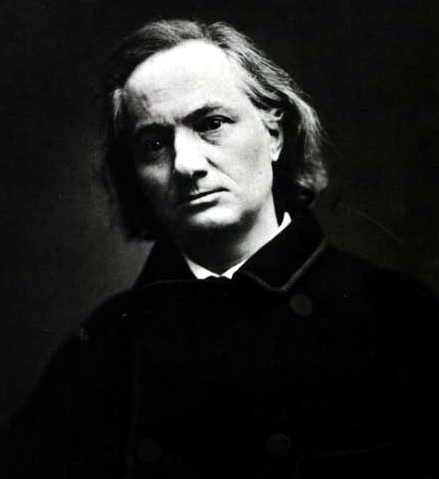

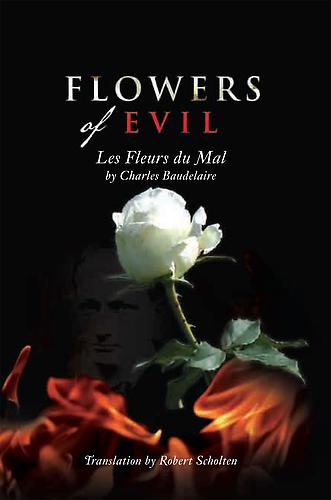

How can a poem be fragrant and a perfume speak poetically? For many of us this poses a confusing enigma. Not for Charles Baudelaire, arguably the most brilliant poet of nineteenth century France and father of modern poetry. He gave olfaction a unique place in his writings and elevated it to a stature never before seen in the history of poetry. Dubbed “un...gourmet d’odeurs” (a gourmet of odors), for him perfume was timeless and much adored (7, 10). His most original contribution was to render fragrance a mode of aesthetic perception evoking poetic inspiration (9). It was also a means of perceiving beauty, experiencing spiritual ecstasy, creating inner worlds, and transforming the body.

Both language and perfume intermingle with the breath, one essential reason for their reciprocal expression. Inhale, exhale, inhale again, and the perfumed word, riding on the rhythms of respiration, spreads its scent and speaks its poetry into the transformed consciousness of both poet and reader. You can feel and see such transformation happening in this poem by Baudelaire:

Exotic Perfume

When, on our late, hot autumn afternoons,

Eyes closed, I breathe your breast’s warm,

heady scent,

I see a sun, fixed in the firmament,

Shining on dazzling shores: strand, rolling dunes;

One of those lazy, nature-gifted isles,

With luscious fruits, trees strange of leaf and limb,

Men vigorous of body, lithe and slim,

Women with artless glance that awes, beguiles,

Lured by your scent, led on to charming clime,

I see a port, all mast and sail,

Battered and buffeted by tide and time;

And all the while green tamarinds exhale

Perfumes that fill my nostrils and my soul,

Blending with sounds of sailors’ barcarole (1).

The research for this article has taken me on an extensive, factual and fascinating journey through the aromatic literature on Baudelaire. For those interested in the journey, here are the highlights along the fragrant road of the perfumed word:

1. Baudelaire, Charles. Les Fleurs du mal. Translated by Richard Howard. Boston: David R. Godine, 1982.

2. Baudelaire, Charles.Selected Poems From Les Fleurs du mal.Translated by Norman. R. Shapiro. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

3. Baudelaire, Charles. The Flowers of Evil and Paris Spleen. Translated by William H. Crosby. Rochester: BOA Editions, 1991.

4. Bendeth, Marian. Basenotes, “Fragrance Delecto: The Scented Mask of Kilian Hennessy. May 2008.

5. Classen, C., Howes, D., & Synnott, A. Aroma: The Cultural History of Smell. New York: Routledge, 1994.

6. Classen, Constance. The Color of Angels: Cosmology, Gender and the Aesthetic Imagination. New York: Routledge, 1998.

7. Corbin, Alain. The Foul and the Fragrant: Odor and the French Social Imagination. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1986.

8. Rindisbacher, Hans J. The Smell of Books: A Cultural-Historical Study of Olfactory Perception in Literature. Ann Arbor:

The University of Michigan Press, 1992.

9. Rhodes, S. A. The Cult of Beauty In Charles Baudelaire V1. New York: Columbia University, 1929.

10. Stamelman, Richard. Perfume: Joy, Obsession, Scandal, Sin, A Cultural History of Fragrance from 1750 to the Present. New York:

Rizzoli, 2006.

11. Weil, Jennifer, Wmagazine. “Eau de Rimbaud: A Young Cognac Scion Finds Poetry in Perfume,” October 2007.

gallery.library.vanderbilt.edu. Vanderbilt University

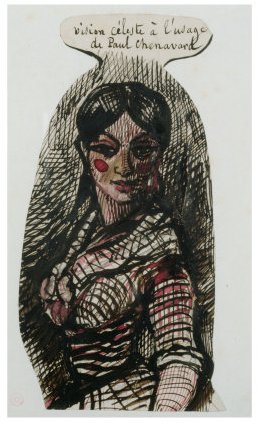

Drawing of Jeanne Duval with an Inscription to Paul Chenavard, courtesy of Art.com

http://www.library.vanderbilt.edu/central/sigaux/Baudelaire/col-exotique-1j.JPG

all additional images supplied by Editor In Chief The Perfume Magazine

Burning Frankincense

Ambergris

This poem finds its very words rising from within the “warm, heady scent” of his beloved’s breasts. He breathes in her fragrance, and the power of the scent draws him inward. Baudelaire closes his eyes. All senses turn from the external to the internal world. His poetic imagination becomes fired, and he creates a dreamlike, island paradise comprised of sounds, sights, smells, and touch. As readers we experience along with him the warmth of sunlight, the textured sands of rolling dunes, vigorous, men, beguiling women. The island holds the fullness of existence, yielding both the vitality of life in its climate, plants, ocean, and people, as well as the movement toward death in its battered port “buffeted by tide and time.” Penetrating and unifying all the images is the omnipresence of the scented word. In the final stanza he stresses that “all the while green tamarinds exhale/Perfumes that fill my nostrils and my soul (italics added).” The tamarinds breathe their scent into the poet. As they do so, the words themselves seem to lift from the page, breathing a green-colored fragrance into the reader’s air. Finally, the perfumes meld with the sounds of the sailors’ song, becoming the poetic word.

The perfumed word transforms the poet’s body as it transports him to mystical dimensions. It is an immaterial vehicle of passage (10). While writing about “Exotic Perfume,” Stamelman states that perfume “renders the familiar unfamiliar; it mystifies the commonplace: an autumn evening of love...turning the ordinary into the extraordinary.” The poet experiences an “extravagant and extraterritorial...ecstasy” accompanied by “a delightful disembodiment whereby the...body and soul become an airy, vaporous reality.” Eyes closed, senses turned inward, the fragrant word intermingled with his breath, the body of the poet undergoes a volatilization that opens onto the spiritual (10).

Perfume, poetry, and transfiguration are intimately, inextricably connected. Like the spirit, scent penetrates self, body, and world. It is formless, ephemeral, unfixed, “and moves ineluctably toward disappearance (10).”

Baudelaire’s understanding of correspondence, a term coined by him, lays the ultimate groundwork for the existence of the perfumed word. It is the experience of synesthesia, “through which information provided by one sense if filtered, interpreted, and ‘read’ through the medium of another.” His “dream of a sublime poetry” involved “...colors, as dazzling in their scent as in their sound, and...scents animated by an odorous spectrum of colors and by a scale of aromatic notes -- as resonant with hues of red, blue, and yellow as they are with chords of jasmine, iris, and patchouli....(10)”

For Baudelaire more than the senses correspond. The spiritual is immanent in the natural world, not just transcendent to it. He wrote, “Everything --form, color, number, perfume -- in the spiritual as well as in the natural world is meaningful, reciprocal, converse, and correspondent....(10)” The spiritual world and the natural world form a unity, as do the sounds of distant echoes coming together into one unified, symphonic sound. Here is a portion of his most well-known poem on the subject, aptly entitled, “Correspondences:”

As distant verberating echoes can resound

Together, mingling deep and shadowed harmony

As vast as midnight and as vast as clarity,

So can each scent and hue and sound to each respond.

Some perfumes are as fragrant as an infant’s flesh,

Sweet as an oboe’s cry, and greener than the spring;

-- While others are triumphant, decadent or rich,

Having the expansion of infinite things,

Like ambergris and musk, benzoin and frankincense,

Which sing the transports of the mind and every sense (2).

Baudelaire's Mistresses in his life, artwork by Baudelaire

All of these experiences of synesthesia bring pleasure, a sense of peace, and harmony with the world. There are others that are darker, having to do with heavier, more powerful fragrances and perverse recesses of the human psyche; still others elicit spiritual and creative aspects of existence. Ambergris is a secretion coming from the intestines of the sperm whale. Musk, also a secretion, is produced in excretory follicles under the abdominal skin of the male musk deer (Moschus moschatus). These are both fecal, animalic fragrances and evoke decadent instincts and emotions, such as lust, greed, sloth. Stamelman writes, “these fragrances emanate from Baudelaire’s ‘flowers of evil’ or from the dark void of existence...and its aroma of absence (10).” They open onto an infinite of boredom and suffering. Benzoin and frankincense are gummy resins, collected as seepage from trees. These scents alter consciousness, culminating in mystical states. Theirs is an ecstatic, luminous infinite.

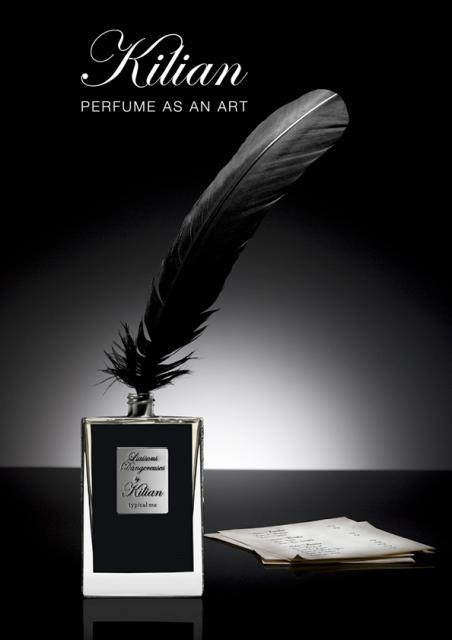

The contemporary perfumer who most clearly falls within the heritage of the perfumed word is Kilian Hennessy. He describes Baudelaire as “One of the greatest French poets...of smells--of perfumes....(11)” Hennessy integrates poetry into the very concept of his collection, L'Oeuvre Noire (Black Masterpiece), in which several perfumes are named after poems by Baudelaire, Rimbaud, and Verlaine (11). Marian Bendeth captures the synesthesia in his creations, “wicked” and more refined lyrics mingling to form accords for unique fragrances: "...L' Oeuvre Noire is predicated on the vision of Faust meets Baudelaire imagery, a poetic come philosophical olfactory vision. Hennessy’s...passion for French literary giants and Greek mythology are carefully blended with the notion of wicked rap lyrics of a Fifty Cent or Lil’ Wayne who use the word “Henny” as the punch in their lyrics. This vision provides a dark moody stomping ground...and juxtaposes edgy accords...with...luxe (4)".

Baudelaire’s vision of olfactory correspondences lives on in the contemporary scene through Hennessy’s creations. The poet has revealed, for generations to come, that the perfumed word, and by implication, perfume itself, is not mere fashion but a powerful living force, metaphysical in nature and impact. It unveils the infinitely dark recesses of the human spirit as well as its mystical epiphanies. If we breathe deeply into its enveloping embrace, perfume will open us to beauty, infinity, and poetic inspiration, while transfiguring our emotional, physical, and spiritual life.

Kilian Hennessy

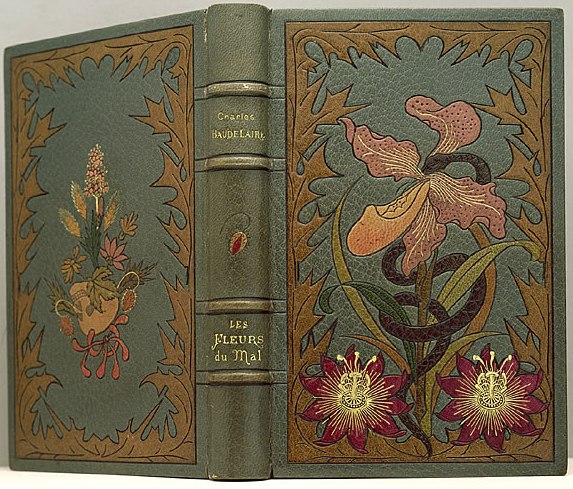

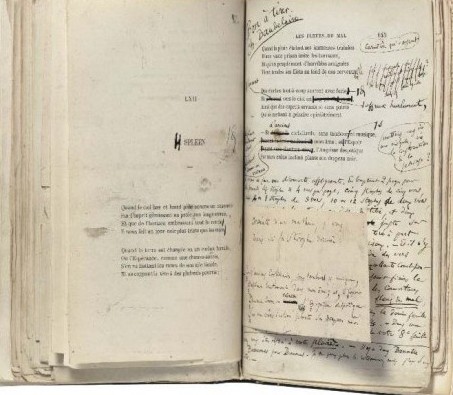

Original edition of Les Fleurs du Mal, complete with author's notes

“Correspondences” teaches us how, depending upon its fragrance, the perfumed word evokes synesthesia. For example, perfumes “greener than spring,” smelling of grass, hay, and lush forests, involve the visual through their evocation of green grass, leafy trees, and bushes. Touch emerges in the recollection of soft spring breezes and rain. The latter leaves a gentle thrumming sound as it falls on houses, earth, and streets. The fragrance of an infant’s skin intertwines with the sight of pink, chubby flesh, and the feel of perfectly smooth, soft skin; tiny whimpers echo through the scent. The sweet oboe cries out aurally with the touch of its velvet tremolos. Stamelman points out its relationship to floral fragrances (10).

Charles Baudelaire

Baudelaire's Notes and Sketches

"Parfum Exotique" image. "Parfum Exotique" was inspired by Baudelaire's mistress, Jeanne Duval (above)

Portrait image by Paul Chenavard