December 30, 2011

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author and/or guest contributors and do not necessarily state or reflect those of

The Perfume Magazine LLC, Raphaella Brescia Barkley or Mark David Boberick.

All content included on this site, such as text, graphics, logos, icons, videos and images is the property of The Perfume Magazine, LLC. or its content suppliers and protected by United States and international copyright laws. The compilation of all content on this site is the exclusive property of The Perfume Magazine, LLC. and protected by U.S. and international copyright laws.

The Perfume Magazine Banner was designed exclusively by GIRVIN and is the property of The Perfume Magazine, LLC. and are protected by U.S.and international copyright laws. Additional Banner information can be found on our ABOUT page.

All images appearing in the banner are registered trademarks of their respected company and are used with permission.

© Copyright. 2011. All Rights Reserved. The Perfume Magazine LLC

Co-Founder, creator and artist of A Dozen Roses, Sandy Cataldo, signing bottles

On Making Sense out of Scents

by Elena Vosnaki

Top notes of honey flower and solar musk. Heart notes of Osmanthus and Amberlyn. Base notes of tactile woods and vetiver. Does this random perfume notes list, replete with sensuous innuendo, make absolutely no sense to you? It might be unicorn tears and rainbow ends for all you know! Likewise, in front of an aromatic stanza, we're often at a loss to accurately describe what we smell to another.

Apparently, dear reader, you're not alone; the confounded crowd includes tons of perfume lovers who struggle through perfume descriptions on a regular basis. It's hard to make sense out of scents...

The Situation: Introduction to Confusion

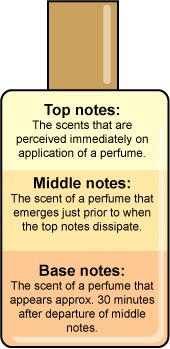

Consider flipping through a fashion magazine for a minute: Sandwiched between glossy pages of advertising with models in ecstatic surrender to the sheer beauty of any given potion of seduction, you will find editorial guides that teach you that fragrances are classified in olfactory "families" and that they develop like music "chords" into top notes, heart notes and base notes, built into a "fragrance pyramid": maximum volatility* ingredients first; medium-diffusion materials following them after the initial impression vanishes; tenacious, clinging for dear life materials last. That should make it easier, right? Well, not exactly.

The thing is most contemporary fragrances are not built as neatly and the bulk of fragrance descriptors are written with a marketing consideration to begin with. It's not a plot to mislead, but the industry is still shrouded in mystery, offering a rough blueprint rather than an analytical Google map into the largely uncharted terrain of fragrance composition. So how does one go about it?

The Fragrance Pyramid and Other Myths of Mysterious Structure

This compact form, like a musical sonata, has a clear progression of themes, from elegantly sour to resinous/sweet, down to mossy/earthy, but all work together in simultaneous harmony, becoming more than the sum of their parts. On top of this basic skeleton perfumers may add flowers, fruits, grasses or leather notes, giving a twist to this or that direction like a shift to a kaleidoscope; this allows them to flesh out the core's striking bone structure, just like makeup accents luscious lips and expressive eyes over solid jaws and prominent cheekbones.

Not every fragrance is built on the pyramid structure (or the "chypre accord" for that matter), nor is it a foolproof guide of deciphering a perfume's message. Guerlain's Après L'Ondée (1906) plays with the contrast of warm & cool between just two main ingredients: violet and heliotrope; the rest are accesories. Comparing Guerlain Shalimar (1925), Nina Ricci L'Air du Temps (1948) and Lancôme Trésor (1990) we come across three different styles of composing, of structuring a fragrance: The first is reminiscent of older-style fixation of natural ingredients (lots of bergamot) via the triplet of animal products (civet, more of which below), balsamic materials (benzoin, Peru balsam) and sweet elements (vanilla, tonka bean). The second is pyramidal. The third is almost linear, the same tune from start to finish, a powerful message on speakers.

In linear fragrances the effect is comparable to the unison of a Gregorian chant: the typically fresh top seems entirely missing, replaced by trace amounts of intensely powerful materials boosting the character. Lauder's White Linen or Giorgio by Giorgio Beverly Hills are characteristic examples. Grojsman was in fact the one who introduced this minimalist style with maximalist effect, composing an accord of 4-5 ingredients that comprise almost 80% of the formula (as in Trésor, based on a formula originally made for herself). This accord was then flanked by other materials to provide richness and complexity.

Recalling Pharaonic mysteries more than hard science the term "fragrance pyramid" entered the vernacular as a means to educate the public into how perfumes are actually constructed. It was legendary perfumer Jean Carles (Shiaparelli Shocking, Dana's Tabu and Canoe, Miss Dior) who used this stratagem to explain a perfume to an industry outsider. The "fragrance pyramid" concept embodies the classic three-tiered French structure of such great perfumes of yore as Ma Griffe by Carven (another Jean Carles creation) or Bal a Versailles (Desprez), where the denouement reveals distinct phases resembling a 3-D presentation. You get all different angles while the perfume dries down on the skin; a slow, engaging process to an often unexpected end.

Jean Carles 1892 - 1966 (mcmcfragrances.blogspot.com), Jean Claude Ellena desk house at Cambrais (howtospendit.com), fragrance pyramid for Bal a Versailles (jardanel.wordpress.com), Bal a Versailles ad (jardanel.wordpress.com), penelepe cruz tresor perfume ad (personal-shopping-service.com)

synthetic-musks collage with sketch of deer musk (whatmenshouldsmelllike com)

All other bottle images supplied by Editor In Chief

Consider too one of the tightest traditional structures, the "chypre" (the name derives from the homonymous archetype perfume by Francois Coty, in turn inspired by the ancient blends from the island of Cyprus, i.e. Chypre in French): a harmonious blend (i.e. an accord) of

• bergamot (a citrus fruit from the Mediterranean basin)

bergamot (a citrus fruit from the Mediterranean basin)

• labdanum (a resinous extraction from rockrose) and

labdanum (a resinous extraction from rockrose) and

• oakmoss (a lichen from oaks).

oakmoss (a lichen from oaks).

Times have changed, fragrance launches have multiplied like Gremlins pushed into the ocean and consumers' attention span has withered to a nanosecond on which to make a buying decision. No wonder contemporary perfumes are specifically constructed to deliver via a short cell-phone texting rather than a Dickens novel published in installments in a 19th century periodical. Other considerations, such as robot lab compounding, industry restrictions on classical ingredients due to skin sensitizing concerns and the minimalist school of thought emerging at the expense of Baroque approaches, leave recent launches with increasingly shorter formulae. But that's not de iuoro bad either. One of the masterpieces of perfumery, Mitsouko, consists of a short formula! A succinct, laconic message.

Some fragrances are built like a contrapuntal Bach piece and others like Shostakovich: Comparing a fragrance by Jean Carles or Edmond Roudnitska with one from Sophia Grojsman or Jean Claude Ellena are two different experiences. That does not mean that contemporary perfumes are devoid of architectural merit. On the contrary. Refined compositions like Osmanthe Yunnan or Ambre Narguilé (both boutique-exclusive Hermès) showcase the potential of this school.

Jean Carles

Structure is not only given by arranging the volatility of ingredients. It's how each material plays its delineated role into achieving the overall fragrance. Structure is consolidated by using the requisite materials and ratios to provide what is commonly referred to as "the bones" of a fragrance. Most often these materials happen to be synthetic, because they consist of a single molecule (in contrast a natural, such as rose absolute, can contain hundreds of molecules), they're stable and produce a closely monitored effect in tandem with other dependables. For instance Grojsman's Trésor uses a staggering 21,4% of Galaxolide, a synthetic "clean"/warm smelling note. Jean Claude Ellena is famous for maxing out the technical advantages of woody-musky ingredient Iso-E Super in his fragrances for structure and diffusion.

After all structural analysis is for the professionals. The wearer can experience the fragrance linearly, circuitously or languidly; it ultimately depends on his/her sensitivity, perception, attention-span and education.

Scent Notes Lists & Fragrance Vocabulary: What They Mean and What They Don't

One of the major misconceptions about fragrance descriptors is that the notes lists stand for actual ingredients rather than an "evoked" smell. This is a common cause of hair-tearing despair at the perfume counter when the sales assistant insists that the banana you're smelling in a given perfume just isn't there. Who's right? (Probably your nose, banana is a natural facet of both the jasmine sambac blossom and of ylang-ylang flowers)

Edmond Roudnitska

Jean Claude Ellena

Sophia Grojsman

Other fragrance notes suffer other fates: A few are considered semi-taboo to be mentioned in the description of a fragrance, either due to ethical concerns or due to a very specifically tainted image they impart.

For instance: What is musk, but an effort to mimic the scent of arousal? Consequently an elegant, upscale, ladylike floral launch that aims at a specific demographic might omit to mention its inclusion even though it might be full of it. Linda Pilkington of niche British brand Ormonde Jayne mentioned in an interview to me that her luminous incense oriental Tolu contains civet, an ingredient from the anal glands of the civet cat which "opens up" the floral bouquet much like warm air opens the fragrant notes of a full-bodied red wine. But you won't find that in the press material: "Women don't like to hear an ingredient with a fecal reference enters their expensive perfume!" she laughs.

Synthetic musks in particular are the bread & butter of modern perfumery, not only used in suggestive and sensuous mixes; "clean" smelling variants areexceedingly common too (reminiscent of laundry detergents, fabric softeners and "dryer sheets", because they were used there due to their hydrophobic properties, which meant they stuck on fabric; the association of these scents with "clean" has since stuck). These are largely responsible for the desired "just out of the shower" impression (smell the effect in Glow by JLo or the Clean brand, which even has a fragrance named Clean Laundry and another called Shower Fresh for men). Clearly in the words of indie perfumer Mandy Aftel we've gone through an era of olfactory Puritanism.

This omission of some more risqué ingredients bypasses a double-edged sword: Having to first appease the consumers who are in arms about animal rights (Musk was traditionally derived from the small deer musk from the Himalayas, though now all perfumery musk is synthesized, and civet is harvested by irritating the civet cat into producing the pheromone substance). Plus those people who insist on their commercial perfume being superior because it only contains natural ingredients; that's what they have been told time and again, not necessarily entirely truthfully.

Some flowers mentioned in lists do not even yield essential oil or that yield is so unsubstantial as to render the whole exercise futile. Lily of the valley and gardenia are such examples: Diorissimo, an iconic lily-of-the-valley fragrance, is built on hydroxycitronnelal, geraniol and phenyl ethyl alcohol. Yves Rocher's realistic Pur Desir de Gardénia is built on jasmolactones (materials that resemble the creamier aspects of jasmine). There's an a propos anecdote in the industry about legendary perfumer Bernand Chant producing a non-freesia-containing "freesia floral" for the florist Antonia Bellanca; she had demanded a scent based on freesia going on the living flower's ability to knock one's socks off "like trumpets in an orchestra". Violet scents in turn are based on ionones, materials isolated in 1893, with a powdery/earthy, iris-like scent; violet is too shy to extract adequately. Sometimes an actual natural ingredient exists and its yield is satisfactory, but depletion/sustainability issues leave perfumers with the dire need of a convincing substitute: Mysore sandalwood, traditionally the best variety from India, is an endangered species.

It' likewise totally out of the question, for reasons discussed, to mention Methyl Anthranilate (grape/berry note like in Kool-Aid): the alternative sounds ever so much more welcoming! Would you like to see Calone and Dihydromyrcenol mentioned in the "notes" of your Aqua di Gio, CK One and Cool Water or would you prefer to read "succulent melon" and "sparkling citrus"? Mugler's Angel and Aquolina's Pink Sugar made Ethyl maltol, the flavor of cotton candy & the caramel note par excellence, a household reference. Some salicylates smell of suntan lotion (often referenced as tiare flower or solar notes in descriptions); triplal of green, cut grass; coumarin (derived from the tonka bean) of newly mown hay & almonds. But the familiar reference is much more understandable, easy to grasp and connect to. And perfume marketing is above all about connecting the consumer to a fantasy.

Is Understanding Perfumes a Lost Cause Then?

In many ways, perfume relates to emotion and what we feel upon smelling a fragrance undeniably has the power to transport us; to our childhood bed cradling our favorite doll for comfort, to a journey to mistry Venice in Christmas time, to the surreptitious kiss on the cheek from a cologne-wearing man we secretly had a crush on for ages...

The limited scope of smell transliteration into words, i.e. the difficulty of rationalizing the sensual world, isn't helping along. What is lacking is a solid smell education from a very young age and a shared vocabulary in which perfume makers and perfume wearers will find common ground to tread on to the betterment of both worlds.

*Ingredients are indeed classified in order of volatility in the charts by W.A Pucher and Jean Carles.

This latter fallacy brings us to another phenomenon; perfume launches with notes of vague or imaginatory descriptors. It's more reassuring and transporting to mention that jasmine comes from old-timer Grasse town (historically the centre of perfume production in France since the age of Catherine de Medici) instead of mentioning Hedione, an isolate that smells of the greener part of the jasmine vine (first used in Eau Sauvage; you might see it listed as "transparent jasmine").

"Blond woods" or "cashmere woods" are as vague a term as possible: In reality they denote the presence of Cashmeran, a popular molecule with a spicy, suede-soft, woody scent that reinforces floral notes. Amber & woods might imply Ambrox, an ingredient in many launches, from older D&G Light Blue to as recent as Calamity J and French Lover (by niche brands Juliette has a Gun and éditions des parfums Frédéric Malle respectively).