Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author and/or guest contributors and do not necessarily state or reflect those of

The Perfume Magazine LLC or Raphaella Brescia Barkley.

All content included on this site, such as text, graphics, logos, icons, videos and images is the property of The Perfume Magazine, LLC. or its content suppliers and protected by United States and international copyright laws. The compilation of all content on this site is the exclusive property of The Perfume Magazine, LLC. and protected by U.S. and international copyright laws.

The Perfume Magazine Banner was designed exclusively by GIRVIN and is the property of The Perfume Magazine, LLC. and are protected by U.S.and international copyright laws. Additional Banner information can be found on our ABOUT page.

All images appearing in the banner are registered trademarks of their respected company and are used with permission.

© Copyright. 2012. All Rights Reserved. The Perfume Magazine LLC

June 6, 2012

Exploring Masculinity in Perfumery

by Clayton Ilolahia

Men's Editor

Finding an appropriate language to describe perfume is one of the key challenges a perfume fan is faced with today. Because the Internet has become the main portal for discussion in the 21st century, sharing an impression of a perfume with someone across the world via a blog or public forum can be challenging, especially if the audience does not have firsthand experience of the perfume you wish to share. Discussing top, middle and base notes gives a rudimentary understanding of a perfume’s structure but it has no ability to convey the emotion or imagery that comes from smelling the perfume. To say a fragrance contains notes of bergamot, lavender and musk gives the reader some idea of the olfactory experience but there is a canyon of information missing. Gender is one aspect of a perfume that cannot be described in this way, after all, bergamot, lavender and musk are found in fragrances designed for both men and women. If gender is not embodied in the raw materials that perfumers use, it can be assumed that the language of gender is the result of the perfumer’s hand; gender is written into a fragrance by the perfumer. And just as language evolves, so do the ever-shifting markers that define a fragrance’s gender.

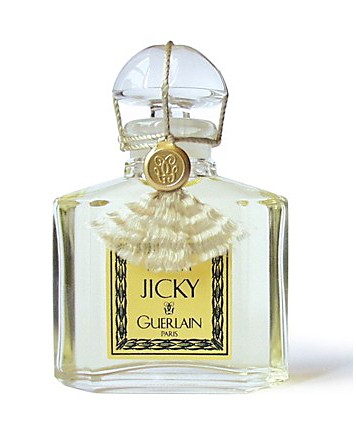

Take Jicky as an example, created by Aime Guerlain in 1889. At first it was men who appropriated Jicky as a symbol of their masculinity. When Jicky was launched, women did not identify with this new style of perfume that was so different from the floral bouquets, which they were accustomed to. It was not until the 1920s that Jicky found its home on feminine skin. As culture evolves, so does the language of perfume. Today there are basic rules that govern the gender of fragrance. Heavy resins, woods or leathery quinolines can colour a floral note with a sense of masculinity. The same floral note paired with aldehydes and musk will be defined as feminine. Just as language utilises grammar to organise words, perfume has its own grammar. I recently took up French lessons to prepare for a summer holiday to France. I soon discovered that in French, gender plays an important role in speaking correctly. Unlike English, nouns are clearly prescribed gender.

French adjectives have both a masculine and feminine form, therefore a tree, which is masculine, is described as vert or green. But a green flower, which is feminine, is described as verte. To know why the French decided trees were masculine and flowers were feminine would require the expertise of a linguistics historian. To understand how the semantics of odour evolved and how perfume was given gender requires a little more than a century of exploration.

Going back to the end of the 19th century when Aime Guerlain created Jicky, it was an era that is now referred to as the birth of modern perfumery. From that time, perfumers began to create abstract works of art; a perfume became conceptual instead of being the smell of a single flower such as violet or rose. Coco Chanel famously said that roses smell nice, but she did not understand why a woman would want to smell like roses. Women are not flowers. She requested perfumer, Ernest Beaux to make something that was entirely new, something mysterious. In 1921, Chanel gave the world No. 5 and it has been a symbol of femininity ever since. By this time, masculinity had already been cast as a powdery fern.

It is a style of perfume that influenced Jicky and is a key reference point for countless men’s fragrances over the 20th century. In 1882 the house of Houbigant created Fougere Royale (Royal Fern). This men’s cologne has a perfume accord made from lavender, oak moss, floral notes and coumarin; a powdery gourmand molecule derived from tonka beans. Its design proved so popular for men that the name was used to group an entire family of perfumes. Today, a man’s fragrance, which is built around this classic perfume accord, is referred to as a fougere.

After the success of Jicky and many other perfumes, which shaped the way 20th century women smelled, Guerlain reconnected with men in 1959 by creating Vetiver, a perfume authored by fourth generation Guerlain perfumer, Jean-Paul Guerlain. His choice of olfactory language was the vetiver rhizome, an odour that is resplendently masculine and filled with dynamic tensions. Jean-Paul Guerlain used vetiver’s earthy quality with hints of tobacco and he enveloped it in freshness. The imagery, which inspired Guerlain is that of a gardener working the soil as he enjoys a tobacco pipe. The scent of vetiver has become another symbol of masculinity due to the raw yet sophisticated quality it can give to a man’s cologne. The signature it offers is often so powerful, many perfume houses, like Guerlain choose to use the raw material’s name as the title of their fragrance.

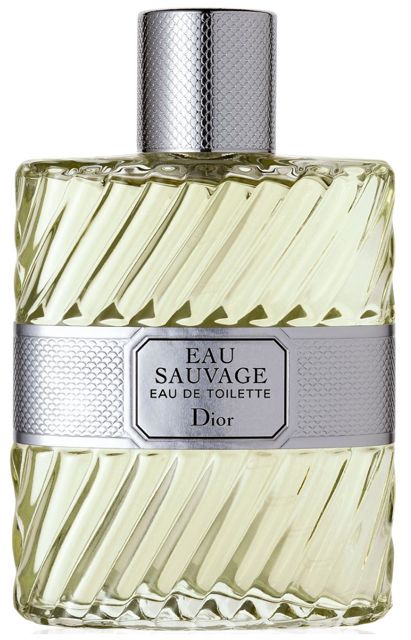

In the decade that followed Christian Dior launched Eau Sauvage, which first appeared in Dior boutiques in 1966. Engineered by perfume master, Edmond Roudnitska, it is reminiscent of a citrus eau de cologne, until the hesperides layers of bergamot and lemon dissolve away to reveal something much more complex and mysterious. I questioned female friends on what their ideal man should smell like; the word mysterious came up on more than one occasion. It seemed many of my female friends enjoyed the company of a man who presents himself as straightforward but a few layers deeper, he shows complexities that were not visible on the surface. Many of the classics in men’s perfumery have the ability to cast this mysterious veil upon their wearers. In the case of Eau Sauvage, it begins with bright citrus notes and a soapy jasmine accord- a man who is fresh, happy and enjoying life. Edmond Roudnitska famously utilized the molecule Hedione, which at the time, was a new addition to the perfumer’s olfactory palette. Hedione adds light and radiance to the heart notes of Roudnitska’s playful creation. As the fragrance progresses Eau Sauvage leaves a virile impression of lavender and darker notes of moss and vetiver.

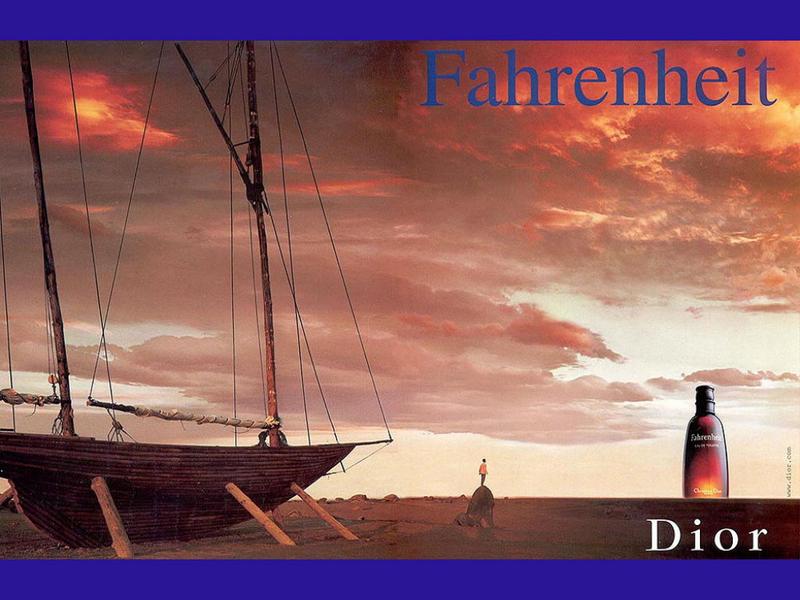

In 1988, Christian Dior was responsible for another milestone in men’s perfumery. Although Fahrenheit is worlds away from Eau Sauvage in terms of olfactory profile, it shares a similarity in that it pairs a traditional masculine theme of earthy woods and fresh citrus notes with an innovative floral accord. Fahrenheit maintains the notion of strength and virility set by its masculine predecessors, with notes of wood, leather and resin but the dominant floral accord, built around violets was an innovation of its time and it also showed a shift in the perception of masculinity that even virile men wear flowers. This shift continued to move and in the following decade men’s cologne had slimmed down. Heavy accords of woods, leather and moss were no longer favourable and masculinity took on a clean, fresh image. Known as the aquatic or ozonic family of fragrances, themes of clean water and fresh air became the imagery linked to men’s fragrance and they became an accessory that could be used after exercise instead of aftershave that was applied only once in the morning after shaving.

As language evolves to meet the communication needs of an ever-changing world, perfume also evolves to stay relevant to its audience. This week I discussed perfume with a male in his mid 20s. For him, Eau Sauvage was a foreign concept. I asked him what his ideal perfume would smell like and his response was intriguing, reinforcing my theory that men and masculine ideals have again evolved in recent years. His own personal body scent was as important as the fragrance he wore. His expectation was that an ideal fragrance would work in harmony with his own scent. Last century men wore perfume or cologne like clothes. Perfume was a scented veil that bolstered the illusion of masculinity. A 21st century man seems much more inclined to believe in a fragrance that does not mask who he is, but gives him more confidence to be himself.

While Marc Jacobs speaks to one type of male, Frederic Malle’s French Lover, or Bois d’Orage, as it is known in Anglo-Saxon countries, presents a niche ideal of masculinity. In his book, On Perfume Making, Frederic Malle discusses his intention for French Lover to become a timeless and elegant scent for men. “We are careful to stay away from scents that reeked of testosterone, the kind that some men wear to prove their virility”. French Lover is wonderfully unpretentious yet it is elegant and sophisticated. The growth of niche or artistic perfumery in the past decade has been an important movement in the perfume industry. Not only do niche brands open up the possibility to use rare and unusual raw materials, their scale of distribution allows them to explore ideas that may not be embraced by a larger audience. French Lover is no smooth charmer, like the man who wears Eau Sauvage. It has a brutal masculinity owing to the high doses, perfumer Pierre Bourdon incorporated into his perfume’s formula. Generous amounts of patchouli, Karanal, incense and musk were added to give the fragrance a raw animal quality, which translates as 21st century masculinity. The quirky name came from a friend of Frederic Malle who commented on a trial version the brand’s founder was testing on himself when the two met for lunch. She greeted him with a kiss and commented, “Tres French lover” as she picked up the scent on Monsieur Malle’s skin. French Lover was released in 2007 and is classified by Michael Edwards as a Crisp Mossy Woods/Chypre fragrance.

This constant dialogue between the perfume industry and the public is a dynamic conversation that enables perfumers to rework the meanings of the materials they use as they observe and converse with the world around them.

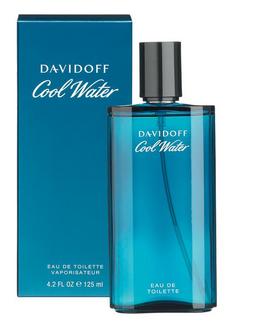

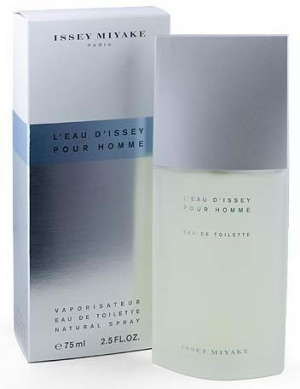

In the 1990s, the sporty cologne was an important market focus and men’s fragrances such as Davidoff Cool Water, Issey Miyake L’Eau d’Issey Pour Homme and Giorgio Armani Aqcua di Gio were the forerunners of this perfume movement, which is still evident in today’s men’s market.

One of these new generation perfumes appealing to a younger male audience is Bang by Marc Jacobs. The American designer understands this target market well. All over the world his Marc by Marc Jacobs brand is coveted by the late teen to early 20s demographic. The title sets the tone or mood of Marc Jacobs’ take on masculinity. Jacobs’ explains, “It had to be something I love, that I would wear, that I want”. Created by Givaudan perfumer, Yann Vasnier, Bang is classified by perfume expert, Michael Edwards as a Rich Woody fragrance. The perfume’s central theme is black pepper, which quickly settles to become a transparent wood melting beautifully into skin. Jacobs thought it important to represent the spice as something you would find in everyone’s kitchen- like salt and pepper. There is no olfactory promise of travel to exotic lands as is the case with Hermes’ peppery journey, Poivre Samarcande. Bang’s pepper feels much more familiar, like a favourite pair of jeans or a worn in pair of sneakers.

Throughout perfume’s modern history there are these symbols of gender that perfumers have assigned to the fragrant world around them, just as the French, at some point in time, decided that a tree was masculine and a flower was feminine. But not everyone speaks French and not everyone speaks this language of perfume. This could explain why many women have enjoyed wearing Eau Sauvage and Vetiver for years. I am currently obsessed with Estee Lauder’s Tuberose Gardenia and I am certain I was not the customer Aerin Lauder had in mind during the creation phase of this rich white floral fragrance. Unlike grammar rules that need to be followed, perfume rules are made to be broken. Whether you prefer Frederic Malle’s French Lover, or his feminine equivalent, Portrait of a Lady; both smell fantastic on men and women.

This is a telling sign of the current status of masculinity in fragrance. We are experiencing an era of free love. Men and women are free to love the fragrances that speak to them, crossing the boundaries of both gender and time. Experienced scent lovers are especially adventurous and many men are finding codes of masculinity within fragrances outside of their generation and gender. Leather and classic chypre perfumes that were popular with women in the 1920s to the 1950s have now gathered a cult following amongst adventurous male fragrance fans. It is a following that is fuelled by word of mouth and by the Internet.

The Internet may be a challenging platform to describe odour but it is the perfect directory for searching and discovering perfume titles, which can then be sought out in person. A majority of my recent perfume discoveries are the result of Internet searches and readings of reviews or conversations between fellow scent enthusiasts. Although a universal language of fragrance that goes beyond a citation of perfume notes would further enrich our online conversations, the Internet is a powerful resource. Thanks to those who contribute to its content, it allows readers to research fragrance by title, author, publisher or house and genre. Whether a man decides that his preferred code of masculinity is the mysterious veil of Christian Dior’s Eau Sauvage, or the refreshing odour of Davidoff’s Cool Water, the Internet opens the opportunity to explore the diversity in fragrance that exists and it can provide an experience that may not always occur, shopping in a bricks and mortar retail environment. As the language of fragrance continues to evolve, who knows what the next generation of men will smell like? Globalization and the digital age have had a notable effect on the way we communicate and I have no doubt this will also influence the way perfumers will communicate with us in the future. Just as new words appear in the English language, appropriated from other languages, perfumers will seek out and adopt raw materials from other cultures, extending our perfume vocabulary and offering future generations of men new olfactory experiences with which they may define their masculinity.

CLAYTON ILOLAHIA | Men's Editor